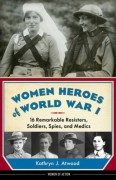

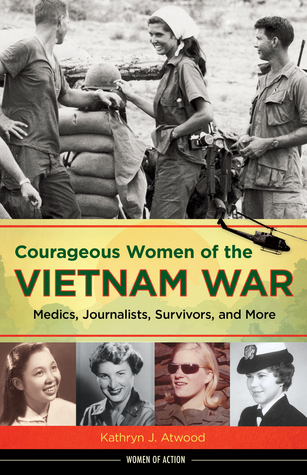

My last book in Chicago Review Press’s Women of Action series publishes soon. I’m supposed to write something to generate interest, so here’s a three-word spiel: Read my book. Now that’s over, here’s a bit more info: this is the second edition of Women Heroes of World War II, a book that has sold pretty well for YA nonfiction, and which I was in the thick of writing exactly ten summers ago. I’m into dates and anniversaries (go figure) so to begin this post I’m going to wind back the clock one more year to the spring of 2008, when I first met Lisa Reardon, my longtime editor. While making a decidedly unsuccessful attempt to musically engage her daughter at the Steckman Studio of Music in Oak Park, I discovered that Lisa was an acquisitions editor for the Chicago Review Press and that she wanted to initiate a young adult women’s history series (Women of Action). Multiple emails and a few months later I signed a contract to write Women Heroes of World War II, the first book in the WOA series.

Energized by this new outlet for my intense desire to research and write, I was also terrified that one or two of the multitudinous facts I was juggling might escape my grasp and crash to the floor. Still, every day I plugged away, always feeling as if I was walking a few feet above the ground, thoroughly inspired by these women who were willing to court death (or worse) in their personal battles against European fascism.

Though invigorating, the effort also proved to be physically taxing, so by the time I handed Lisa the corrected proofs, her suggestion for a prequel book was met with a deafening silence. When my energy returned, I found other reasons for not jumping into a second collective biography. First, I had no idea if the first book would be well-received enough to merit a greenlight for a second. And after writing about Josephine Baker, Sophie Scholl, and Nancy Wake, et al, what historical woman could possible interest me enough to take up the pen again?

There were quite a few, actually. To them in a moment. After it published on March 1, 2011, Women Heroes of WWII received a few obscure but ardent awards (ever heard of The Amelia Bloomer Project, a subgroup of the ALA Social Responsibilities Round Table’s Feminist Task Force? I hadn’t either). Those nods and the generally positive reviews, professional and otherwise, made me realize that I’d been successful enough to write again.

All the books that followed were filled with stories of phenomenally inspiring women who did their best during their nation’s darkest hours: Pearl Witherington, the ultra-calm accidental leader of a French resistance network whose story was included in the first book and whose memoirs I later had the honor of editing; Gabrielle Petit, the First World War Belgian spy who went to a German firing squad defiantly singing the praises of king and country; Louise de Bettignies, who inspired Pearl Witherington and with whom my husband nearly fell in love while he translated the brilliant intelligence organizer’s French language biographical material (It’s ok—she’s dead, our marriage is strong, she had that effect on everyone except maybe the Germans, and I have something to tease John about for the rest of our lives); Elizabeth Choy, the devout and indefatigable Singaporean who wouldn’t lie to her Japanese tormentors, even to save her own life; Aussie nurse Vivian Bullwinkle, the sole and accidental survivor of the Banka Island Massacre; the lovely and compassionate Jane Kendeigh who became the first US Navy flight nurse to land on Iwo Jima and Okinawa; the undaunted and enterprising Dickie Chapelle, who cut her journalistic teeth on the same two islands; Dang Thuy Tram and Lynda Van Devanter, two compassionate medics who worked frantically to save lives on opposites sides of the Vietnam War.

While I’m sure there are more fascinating women of history to be discovered, the last two books, though well-reviewed, haven’t sold nearly as well as the earlier titles. And Lisa--my editor, mentor, collaborator, and friend--no longer works at Chicago Review Press. I received the email bearing this devastating news while I was working on the new chapters for this last book. After absorbing the shock, I returned to my work with the sinking realization that Lisa would not be taking an official editorial look at what I was writing. (The other editors were fine. They just weren’t Lisa.)

I’m grateful for the opportunities of this past decade (and the lengthy acknowledgement section of my last book exhaustively proves this point). Staring down the future without a contract or a highly collaborative editor was, for a few months, a bit terrifying. But I’m finally enjoying my deadline- and contract-free life as I wake up each day to write in sync with the promptings of John Milton’s “heavenly muse” (no, I’m not attempting another Paradise Lost, but one could make the case for a connection). I’m merely staying on top of my craft, prepared for whatever comes next. You might call me a Woman of Action.

Oh, and read my book. Or all of them.

2

2

A River, a People, and a Skyline (from 2009)

When I wrote this recently rediscovered post, my husband and I were in the process of creating our "Chicago History in Song" program, which included my lyrics, "Song of Potawatomi", a version of which was included in the Forest Park Historical Society's "Des Plaines River Anthology."

My high-schoolers have an unusual interest in the weather reports, especially if those reports include heavy rainfall. That’s because their school is just a half-block away from the Des Plaines River, a 150-mile strip of water that stretches from Kenosha to the Kankakee and meanders all through the near-west suburbs of Chicago. If the river gets too high, my kids get a day off.

Even in good weather, and especially if we get stuck – as we regularly do – in Roosevelt Road’s early morning traffic, we always glance at the river as we drive by. Thick clumps of trees and bushes line its banks and grant a visual respite from bumpers and brake lights. I like to think that the river and its bank looked just like that when it provided life and transportation for the Potawatomi.

They were the first Forest Parkers, the folks that traded in the downtown swamp but made their homes next to the Des Plaines River in an area which we also pass on our daily ride, a place currently occupied by many famous and infamous Chicago dead – the Forest Home Cemetery in Forest Park.

The Potawatomi were friendly with the Europeans who moved into the Chicago area: they traded and intermarried with them, and even came to their rescue during the Dearborn Massacre and the Blackhawk Uprising. But the Great White Treaties were apparently made to be broken and the settlers quickly forgot the loyalties of the Potawatomi, kicked them off their own property and sent them packing, many to an area that later became Kansas. Except for a few sad stragglers, by the mid-19th century, the Potawatomi had virtually disappeared from the Chicago area.

It’s a heartbreaking story and I always feel somewhat guilty when I get excited about what comes next: a city rising out of a swamp, like one of those rock gardens that grows to impressive heights when submerged in water. Actually, Chicago was submerged in water, but the rugged early city leaders didn’t let that stand in their way. With a “one, two, three” they lifted the city out of the muck. They reversed the natural flow of the Chicago River. And when the city burnt to the ground in 1871, it was rebuilt it in time to host the impressive Columbian Exposition of 1893. There has never been such a “can-do” city in all of history.

Last Saturday morning, as I was turning east on to the Eisenhower expressway, with my son, heading towards the city, the Forest Park skies were dark and foreboding. But when we passed under the Austin ramp and the Chicago skyline came into view, I got quite a thrill. The clouds behind my favorite buildings were bright with sun and provided a stunning background to one of the world’s more impressive skylines.

After I dropped my son off and headed back to Forest Park, the western skies were still gloomy. And nothing can change the fact that our Chicago predecessors of European descent forced some particularly noble and loyal Native Americans off their own lands. There was a way to build a city without laying a foundation of betrayal and heartbreak. But no one tried to find it. And John and I are going to do our best to make sure that the Potawatomi story is told.

But we’d also like to tell the story of what came next: how sheer determination transformed a swamp into a city. A city with a stunning skyline.

Our daughter's artistic tribute to the Potawaomi on the Circle bridge in Forest Park, part of the village's "cover our rust" art project.

2

2

The Inspiration, Sorrow, and Triumph of the Vietnam Veteran

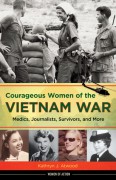

I met Steve Schaefer in the early years of this decade because of our shared association with Pillars of Honor, a Chicago-based organization dedicated to giving a day of honor to World War II veterans too weak to take their Honor Flight. After my husband and I opened each program with World War II songs, Steve, the Pillars of Honor president, would give a few remarks, always introducing himself as a Vietnam veteran, the son of a World War II veteran.

It didn’t take long to connect the dots: Steve’s service had been inspired by his dad’s. And the younger Schaefer was every inch the elder had been, serving three tours in Vietnam and earning four Purple Hearts.

War has always produced heroes, a fact understood by young men of all time. Jurate Kazickas, a combat reporter who witnessed young Americans come under fire in Vietnam, wrote: “War, for all its brutality and horror, nevertheless offered men an opportunity like no other to be fearless and brave, to be selfless, to be a hero.” (1) Like Steve, many of the young men Kazickas met had been inspired by the heroism of the previous generation.

Those fighting on the other side were infused with their own historical perspective. When the Viet Minh defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, they were hailed as national heroes. So it was hardly surprising that the Viet Minh remaining in the south after the civil war began were quickly given a new name by their enemies: Viet Cong, short for Viet Nam Cong San, the Vietnamese Communists. Vietnamese soldiers working for the southern government would be hard pressed to fight with any enthusiasm against the Viet Minh, their own Greatest Generation.

But if war provides an opportunity for heroism, it also, of necessity inflicts wounds. Viet Cong fighters and soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army were patched up by Communist medics in the south who were constantly on the run, changing locations almost as often as they changed bandages. One of these, surgeon Dang Thuy Tram, was moved to give her fallen patients poetic tribute in her diary: “Oh, Bon, your blood has crimsoned our native land. . . . Your heart has stopped so that the heart of the nation can beat forever.” (2)

Thuy and the American nurses featured in my book, Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, couldn’t help becoming emotionally attached to their patients, who, even if they had joined up to become heroes, were reduced to mere boys when wounded. Years after his hospitalization in Vietnam, Air Cavalry Sergeant Robert McCance wrote a note of thanks to his nurse, Anne Koch, acknowledging that he had then “really needed the touch of a mother’s hand.” (3)

Female medics on both sides of the conflict gave that motherly touch. But as Lynda van Devanter, US Army nurse in Vietnam wrote later, “Holding the hand of one dying boy could age a person ten years. Holding dozens of hands could thrust a person past senility in a matter of weeks.” (4)

Anne Koch.

The war wounded these healers. Thuy was killed before it ended. Most of the American nurses survived but suffered decades of inner pain, which matched, or perhaps in some cases outstripped, the outward suffering of their broken, bleeding, dying patients, images that were often etched permanently in the nurses’ minds.

After the war, the eerie silence between the two enemies once locked in mortal combat represented oceans of hurt; all attempts to move past the war seemed hollow when veterans on both sides were suffering. The southern Vietnamese soldiers were given absolutely nothing except, in many instances, a one-way ticket to a cruel reeducation camp. If they were fortunate enough to emerge alive, mere shadows of their former selves, they saw that the new government had obliterated all memorials to their dead comrades.

Post-war life was also bitter for the victors. The rumored riches in the south had been exaggerated and the new country’s economy disastrously unable to provide for its people, much less its fighters. Many female veterans hoped that victory would bring an opportunity to raise a family in peace. But the long, grueling years of war left too many unable to bear children even if they could find someone amid the surviving males to marry them.

Most American female veterans went on to live outwardly normal lives but they, like their male counterparts, received no recognition for many years. This was, perhaps Steve Schaefer’s biggest wound and one that should have earned him—and all the other vets—an additional Purple heart. The inability of family and friends to comprehend what they had experienced, on the one hand, and the lack of respect from strangers on the other, exacerbated the inner pain overwhelming these veterans.

But perhaps the most inspiring stories of the Vietnam War occurred at this point. While post-traumatic stress is as old as combat, the suffering of Vietnam veterans gave it a name. A brotherhood of the war-wounded was formed and, as my book illustrates, a sisterhood as well. Lynda van Devanter founded the Women’s Project at the Vietnam Veteran’s of America. Kay Bauer, a US Navy nurse who was targeted by domestic terrorists after the war, created a PTSD program for female Vietnam veterans in Minneapolis, her hometown. And Diane Carlson Evans, who wrote my book’s forward, spearheaded the difficult ten-year project to honor all the women veterans of the war with their own memorial in Washington, D.C. The unveiling of that memorial on November 11, 1993, was a time of honor, personal healing, and numerous reunions between female medics and their patients.

Many Vietnam veterans, male and female, would eventually succumb to the effects of Agent Orange. Steve Schaefer was one of these. But like so many veterans of that war, Steve had found a way to move forward in his life long before it ended. He led local veteran’s associations and helped the homeless for decades, and in his final years worked tirelessly to give tribute to the generation that had inspired him.

- Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, 89.

- Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, 129.

- Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, 119.

- Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, 145.

Top photo: Jurate Kazickas.

Bottom photos, left to right: Dang Thuy Tram, Bobbi Hovis, Lynda van Devanter, Kay Bauer.

2

2

A diary, a memoir, and a war.

Dang Thuy Tram is pictured on the far left, Lynda Van Devanter second from right.

Because one of my goals in writing Courageous Women of the Vietnam War was to understand the conflict from multiple perspectives, I tried to feature women from different sides within each chronological segment. In the section labeled "Richard Nixon's 'Peace'", I included the story of Communist surgeon, Dang Thuy Tram, and American nurse, Lynda Van Devanter and found them to be movingly similar.

In 1969 Dang Thuy Tram was a three-year graduate from medical school and Lynda van Devanter a newly trained nurse. These young women could have put their skills to use in relative safety but chose instead to serve their countries -- North Vietnam and the United States, respectively--by going into a war zone: South Vietnam.

The United States had just sworn in a new president whose campaign promise had been “an honorable end” to the Vietnam War. Precisely what Richard Nixon meant by those words would not become clear till much later, but nothing he said before his inauguration or anything he did afterwards could shake the resolve of the leader in North Vietnam who remained determined to see Vietnam united. In the same month Nixon began his presidency, Thuy, already working with the VC in the south and longing to be accepted into the Communist party, copied a speech from Ho Chi Minh in her diary:

…This year greater victories are assured at the battlefront. For independence—for freedom. Fight until the Americans leave, fight until the puppets fall. Advance soldiers, compatriots. North and South reunified, no other spring more joyous. (1)

Ideology also spurred Lynda into the war. On night, during her last year of nursing school, she made up her mind to join the army and go to Vietnam, believing that the US was “pursuing a course that President Kennedy had talked about in his inaugural address: we were saving a country from Communism.” (2)

There were brave boys fighting and dying for democracy…And if our boys were being blown apart, then somebody better be over there putting them back together again. I started to think that maybe that somebody should be me. (3)

Thuy traveled down the dangerous Ho Chi Minh trail and landed in the Quang Ngai Province, an area with a history of intense resistance to foreigners. On June 9, 1969, just six months after Thuy recorded Ho’s speech in her diary, Lynda became one of those foreigners, working 244 miles away at the 71st Evacuation Hospital in Pleikuk.

Both Thuy and Linda were involved in life-saving surgeries and both found triage emotionally difficult. Lynda stated it bluntly: “Essentially we were deciding who would live and who would die.” (4) She later described her first experience of a “mal-cal”—a mass casualty situation:

The moans and screams of so many wounded were mixed up with the shouted orders of doctors and nurses. One soldier vomited on my fatigues while I was inserting an IV needle into his arm. Another grabbed my hand and refused to let go. A blond infantry lieutenant begged me to give him enough morphine to kill him so he wouldn’t feel any more pain. A black sergeant went into a seizure and died while Carl and I were examining his small frag wound. (5)

When Thuy’s team decided to not operate on a dying patient, she “conformed to the majority’s opinion” but poured regret into her diary:

He died with a small notebook in his breast pocket. It held many pictures of a girl with a lovely smile and a letter assuring him of her steely resolution to wait for his return. On his chest, there was a little handkerchief with the embroidered words Waiting for you. Oh, that girl waiting for him! Your lover will never come back; the mourning veil on your young head will be heavy with pain. It will mark the crimes committed by the imperialist killers and my regret, the regret of a physician who could not save him when there was a chance. (6)

Thuy never wavered in support of her government’s war aims. While the war was absolute hell for most Vietnamese people, it wasn't hard for Ho Chi Minh's followers to keep their motivations stoked. The US, in their minds, was simply following China and France as the most recent colonizer and the southerners, they thought, were wealthy traitors. Each new Viet Cong or NVA death increased Thuy's hatred for the enemy and her desire for victory.

Every American death had the opposite effect on people like Lynda; it was difficult for the average American serving in Vietnam to maintain their ideological reasons for supporting the war. How was their presence promoting democracy, exactly? Increasingly haunted by the deaths of far too many young Americans under her care, Lynda wrote home, “We should either pull out of Vietnam or hit the hell out of the NVA. This business of pussyfooting around is doing nothing but harm. It’s hurting our GIs, the people back home, and our image abroad.”

The war had a devastating effect on the lives of both women. It ended Thuy’s--she was shot by an American bullet sometime in June, 1970. Lynda boarded her “freedom flight” that same month but returned home to face the hostility of strangers, the misunderstanding and indifference of friends and family, and years of untreated PTSD.

But their stories were destined to have major post-war impact. When Lynda wrote her moving war memoir, Home Before Morning, in 1983, it became a bestseller, inspired the award-winning China Beach series, and illuminated the unique plight of American Vietnam War nurses.

Dana Delany as US Army nurse Colleen McMurphy in the China Beach TV series.

Thuy’s diary was found by an American military intelligence officer who took it home but brought it back to Vietnam in 2005 where it was published that year. There were plenty of war memoirs and biographies in Vietnam by this time, but Thuy’s diary revealed the voice of a flesh and blood human being who questioned her own motives, grieved for the lost, and hoped for an end to the war; she was not a hero carved in marble spouting all the correct sentiments. Last Night I Dreamed of Peace became a bestseller and was translated into English in 2007.

War inflicts wounds not only on those who fight in them but on those who dedicate themselves to heal wounded warriors. Thuy and Lynda paid dearly for choosing the role of healers but they became the voices of their generations, and in speaking from their frame of reference, helped countless readers understand the war from the other side.

1. Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, 125.

2. Home Before Morning: The Story of an Army Nurse in Vietnam by Lynda van Devanter, 49.

3. Courageous Women, 137.

4. Courageous Women, 138.

5. Courageous Women, 142.

6. Last Night I Dreamed of Peace: The Diary of Dang Thuy Tram, 99-100.

7. Courageous Women, 145.

Genevieve de Galard at Dien Bien Phu before the seige.

While the basic concept of all my books is women in war situations, each title was born from a unique motivation. The impetus that brought Courageous Women of the Vietnam War into the world was my desire to (1) understand the complexities of that war’s timeline, and (2) to present stories of women who experienced the war from all sides within the book’s chronological framework.

The first section covers the conflict that was the prelude to the Vietnam War--the First Indochina War—and it features a chapter on a Vietnamese revolutionary and a French Evacuation nurse.

Xuan Phuong was born in 1929 and raised in what the French then called Annam, the central portion of French Indochina. Her family was wealthy as her father was the superintendent of a school, but she had uncles who influenced her with their revolutionary ideals.

Genevieve de Galard was born in 1925 and was also influenced by her family: her uncles and late father had been career officers and her lineage could be traced back to Joan of Arc. She lived through the German occupation of France as a teen and joined the military in 1953 as an air evacuation nurse.

These two women would find themselves on opposing sides of the First Indochina War, a conflict with its roots in World War II. The Viet Minh--the Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi or League for the Independence of Vietnam--worked side by side with American OSS agents as they both fought the Japanese occupiers of Vietnam.

On September 2, 1945, hours after the Japanese surrender to the Allies in Tokyo Bay, Ho Chi Minh, political leader of the Viet Minh, publicly declared Vietnam’s independence from France, quoting the American Declaration of Independence.

Neither France or the United States would acknowledge Ho’s claim; France because it wanted to retake its colonies in an ironic attempt to regain some national dignity after four-plus years of German occupation, and the US because Ho was a Communist, the ideology of their new enemy. So instead of supporting Vietnam’s independence, they supported their former ally’s quest to retake their colony.

Ho’s determination matched France’s and the First Indochina War began. In November, 1953, the French commander-in-chief in Indochina, General Henri Navarre, ordered a garrison in a northern village called Dien Bien Phu held in order to protect his pro-French Vietnamese allies in the area from the Viet Minh.

The denouement of a conflict often boils down to a single battle and the First Indochina War ended here. General Navarre was as myopic as Viet Minh General Vo Nguyen Giap was astute and Viet Minh troops soon moved close enough to shoot down French planes, Navarre’s only planned means of resupply and evacuation.

The exhilarating smell of victory was in the air and Xuan Phuong, employed nearby, caught a whiff:

"Finance Ministry workers excitedly assembled around a large map that depicted combat areas with red pins and French casualty numbers on labels. ‘The atmosphere was electric’ Phuong wrote. The slogan heard and repeated everywhere was ‘We work one and all for Dien Bien Phu.’

Vehicles heading to Dien Bien Phu passed by the Finance Ministry all hours of the day and night: people on bicycles carried their village’s required allotment of rice to the front lines of battle while trucks rolled by loaded with weapons and ammunition. Journalists, writers, and musicians all raced there as well, and Phuong heard many moving stories of long-separated friends reuniting at the front.” (1)

French hope was dying at Dien Bien Phu but Genevieve de Galard, who had arrived on the last plane and was now stranded, did what she could to counteract the deepening despair. She cared for as many patients as possible in the overwhelmed medical units and empathized with their desperate situation:

“I shared with the combatants moments of high hopes, when a position was retaken by our men, and the awful moments, during the heartbreaking adieux of the unit commanders: ‘The Viets are thirty feet away. Give our love to our families. It is over for us.’ My heart tightened as though I were hearing the last words of the condemned.’” (2)

When the war was over, Phuong had to endure the nightmare of a totalitarian society, silently questioning the barbarities of land reform:

“’What have all these long years in the Resistance been sacrificed for? What happened to our lofty ideals?’ Phuong felt as if she were witnessing the utter destruction of a civilization.” (3)

But Genevieve, a new darling of the international press and “the Angel of Dien Bien Phu”, was given a ticker tape parade in New York City and sent on a three-week tour of the US. To her credit, she didn’t let it go to her head, giving speeches along these general lines:

“I haven’t earned this honor, because I only did my duty…My thoughts, at this moment are with all those who are still over there and who, far more than I, have earned this honor that you offer.” (4)

These women went on to live quietly productive post-war lives; they raised families, had careers, and are still with us today: I had the honor of communicating with both while writing this book.

- Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, page 18

- Courageous Women, 31.

- Courageous Women, 20-21

- Courageous Women, 35.

2

2

My search for Rosalie K. Fry

I’ve wanted to write a blog post on Ms. Fry, author of the achingly beautiful story The Secret of Roan Inish, ever since I realized that the lovely film was based on a book. Try Googling her, though, and nothing comes up but the titles of her books. For some odd reason the University of Southern Mississippi has her “papers” and their website condenses her biographical facts into two short sentences: “Rosalie K. Fry was born in Vancouver, Canada, and lived as an adult in England and Wales. She attended school in Wales and in London at the Central School of Arts.”

Wales and the art school explain a lot but only through inference. I thought perhaps purchasing a collection of her books might shed some light and one of them did: the back cover of A Bell for Ringblume offered the following:

“This author was born on Vancouver Island. She makes her home in Swansea, South Wales. During World War II she was stationed in the Orkney Islands, where she was employed as a Cypher Officer in the Women’s Royal Service. She has written many stories and executed many drawings for a variety of children’s magazines in Great Britain. She is also known as a maker of children’s toys. Her books, which she has also illustrated, have included: Bumblebuzz; Lady Bug! Lady Bug!; Bandy Boy’s Treasure Island; Pipkin Sees the World; Cinderella’s Mouse and other Fairy Tales; and The Wind Call.”

Three of my books features heroic WWII women so when I read of Fry's wartime work I immediately gave a hearty huzzah for her. Like so many other women of the time, she had placed her life on hold in order to do battle with Fascism.

When I wrote an earlier edition of this blog post, back in 2012 (www.myenglishfinal.blogspot.com), a fellow-Fry fan in the UK sent me some biographical information on her, a chapter in a "About the Author" book. He also sent me this:

This is the Secret of Roan Inish story, originally known as The Secret of Ron Mor Skerry, but this Canadian version had a slightly different title. I was on cloud nine for about a year.

I've reviewed several of Fry's books and one just arrived in the mail last week. I'd love to write a biography of her but until I find more material I will keep searching within the pages of her fiction for the person who set aside the creation of lovely worlds in order to decode for king and country.

2

2

Why I write young adult collective biographies about women and war: The Booklikes interview

Tell us a few words about yourself - whatever you want to share about your personal and professional life, but also why you decided to become a writer.

I’m a vocalist, music historian (historysingers.com), and piano teacher, and the latter vocation serendipitously led to my becoming an author. I was teaching at the Steckman Studio in Oak Park, IL, when I met Lisa Reardon, a parent who also happened to be an acquisitions editor for the Chicago Review Press. Lisa is no longer with CRP but her wonderful influence can be seen in all of my books.

I first discovered my passion for putting pen to paper while in college. I started out as a history major with an English lit minor then switched halfway through. When I finally allowed myself the time to develop as a writer I wrote poems and essays for some quirky lit journals while reviewing history books and biographies for two review sites. Then I met Lisa.

What inspired you to write about wars? It seems like such a difficult topic, even more so as you've written about many wars: World War I, World War II the Vietnam War ... what is it about the topic of war that interests you?

I’ve been fascinated by World War II since I was a teenager when I watched a show called “World at War” with my WWII Army Air Corps vet dad. The Hiding Place came to theaters at that time as well and it left me with the following question: What sort of person would one have to be, what sort of character would one have to possess in order to defy a totalitarian regime? That question finally found an answer in my first book, Women Heroes of World War II. All the women featured there defied the Nazis to one extent or another.

War brings out the best and the worst in people, which makes it such a fascinating study. But I’ve had specific additional reasons for writing all my books, generally because I want to wrap my brain around a specific war. Courageous Women of the Vietnam War came into being because although I lived through that war as a child I didn’t understand it. Young men in my family circle were going there, my friends and I all wore POW bracelets, but we were taught very little about it. Writing the introductory material vastly improved my grasp of the conflict and writing the narrative chapters allowed me a close-up view through the eyes of women who were there.

Your books are listed as targeted at young adults, teens. Why did you choose this audience?

When I first met Lisa, she wanted to launch a young adult series about historical women which is now CRP’s Women of Action series. So the audience was chosen for me. But as I began writing Women Heroes of World War II the audience I kept in mind was my 12 year-old self—an undermotivated student who loved to read. I was deliberately trying to reach young people who might not believe they like history but who might be enticed towards interest in a particular historical woman if the narrative was compelling. To understand what made that woman tick, one has to understand her setting and voila! The reader is learning history!

What would you say sets your books apart as books for teens, as opposed to other history books for adults? What makes them different? How do you write to make sure you attract your readers' attention, and to ensure that they understand the points you would like to get across?

I try to arrange the facts of each brief chapter in such a way as to get to the heart of the individual person’s story while keeping the narrative moving. In the first book, especially, I tried to start in the middle of the story, then provide some background before continuing with the denouement. I knew I’d hit my stride with Women Heroes of World War II — the Pacific Theater when the Booklist reviewer wrote that each chapter “could constitute a cliffhanger screenplay.”

I’m not really trying to make a point in my books. Aside from the introductory material, I’m merely trying to present history through the eyes of the women who experienced it. I strongly believe that we need to teach young people howto think, not what to think. We need more room for freedom of thought and differences of opinion in this country, on both sides of the political divide! It’s crucial to provide teens with an unbiased view of history for, as the saying goes, those who don’t learn history are doomed to repeat it.

Do you travel to the places you write about in your books? Do you think this is a necessary element of the "job" for a non-fiction writer?

I’ve been asked that question many times! One certainly needs to find a direct connection to history in order to write a good history book, but I believe I’ve managed to do that without traveling. For Courageous Women of the Vietnam War I found that connection through direct communication with the women themselves. One of them, US Army nurse Anne Koch Voigt, sent me a scrapbook filled with mementoes and photos from her year in Vietnam. It was a visual lightning bolt (and I believe her chapter contains the most photos and sidebars of any in the book!)For Women Heroes of World War I I accessed dozens of digitized memoirs and mined them for quotes. In doing this I felt I was giving a voice to these women who experienced war a century ago. It was almost as exciting as my experiences while working on the first book when I spoke on the phone with the following people: George J. Wittenstein, a personal friend of Sophie Scholl; Barbara Moorman, the daughter of Johtje Vos; Nelly Hewitt, daughter of Magda Trocme; Muriel Engelman, a US Army nurse who came under direct fire during the Battle of the Bulge; and Diet Eman. I also exchanged emails with Paul Elsinga, a man who knew Hannie Schaft when he was a boy. All electrifying experiences!

Many of your books focus on women? Why did you make that choice when you set out to write your books?

Again, that’s how I got started, but I’ve continued because I love to illuminate the stories of unsung heroes. There’s a reason we have Women’s History Month; most history, if studied in an overview sort of way, deals mainly with the efforts of men. Men’s stories are like the icebergs of history — their contributions are all that is visible after a particular period of time has passed, but there is so much more going on beneath the surface, so much history left behind. Women’s experiences and perspectives fill in all the blanks and make the picture complete.

Have you read Svetlana Alexievich's book about the role of women in war? Did it inspire you in any way?

I’m halfway finished and I absolutely love it. Again, there’s nothing like the testimony of people who lived through history to bring the reader directly into the past. And I was impressed at how the women interviewed for that book were so human and honest about how their femininity and relative youth intersected with the horrors of war. In that aspect, many of the stories sound similar, but because the women had different roles, The Unwomanly Face of Warhas significantly widened my understanding of the Eastern Front.

I’m halfway finished and I absolutely love it. Again, there’s nothing like the testimony of people who lived through history to bring the reader directly into the past. And I was impressed at how the women interviewed for that book were so human and honest about how their femininity and relative youth intersected with the horrors of war. In that aspect, many of the stories sound similar, but because the women had different roles, The Unwomanly Face of Warhas significantly widened my understanding of the Eastern Front.

2

2

Ulysses S. Grant's bathtub (and the rest of his house).

I’ve recently seen the Mississippi River. And Ulysses S. Grant’s bathtub. Both can be found in northwest Illinois in the lovely little city of Galena where I took my 20-something daughter. Our hotel view of the great river was so magnificent I eagerly set out to get a closer look. But as the bugs emanating from the nearby woods had complete disrespect for insect repellent I gave up quickly, like a city slicker, and contented myself with the beautiful vista from our room and the indoor pool.

I did, however, get fairly close to that bathtub. The modest red-brick house that Grant had once called home was so small I was surprised when Frank, our tour guide, told us that it had been gift from the city of Galena to the conquering Civil War hero. Perhaps it was the best this modest city could do for its most famous son.

Frank showed us the library first. Two of the four walls were covered by glass-encased bookshelves. Many of the books here—and most of the home’s furniture for that matter--had personally belonged to the Grants. Readers often become writers and here was the personal library of the future memoirist whose writing was so good his book has never gone out of print. Any reading would have been done at the round table in the center of the room upon which sat a 15-pound Bible.

Perhaps the room did not reek of comfort, but it most likely smelled of cigar smoke while the Grants lived there: an elaborate waist-high ashtray stood between the window and the table.

The parlor was next. The seats were low to the ground, Frank said, simply because people were shorter back then. All but one of the chairs was black, covered with a woven combination of horse hair and silk, highly durable but apparently uncomfortable. Notably, Grant’s favorite chair, covered with plush green cloth, stuck out like a sore thumb in that room of slightly scary upholstery. Grant was a soldier, first and last, but he obviously enjoyed comfort when and where he could find it. Grant and his wife, Julia, had received crowds of people in this smallish room and I wondered how. Perhaps their Lilliputian stature came into play or maybe they had an affinity for claustrophobic social gatherings.

After leaving the small dining room—the table set with the Grants’ own china—Frank sent us off to tour the bedrooms upstairs on our own.

Grant's bed.

Each of Grant’s four children had their own room, complete with a chamber pot. Who emptied them out, I wondered? The Grants themselves or perhaps their “help.” In the next room, the kitchen, we learned that while the Grants did hire servants, these folks lived elsewhere. Seriously, where would they have put any live-in “help”?

Behind the kitchen was a bathtub, the view of which could be accessed by leaning over the railing in front of the kitchen. “How often do you get to see where a former president took a bath?” Frank quipped. Not often. We all leaned over and took a look. The entire family bathed in this tub and in the same water, beginning with the eldest, a custom not peculiar to the Grant family. Still, eewww.

The house was simple, straightforward, and seemed a perfect fit for the man who had once lived here, someone with little success in civilian life but who was such a natural-born military leader that he became a major force in winning the Civil War for the Union.

1

1

An Ode to Children's Non-fiction

The author reading from Highlights in her parent's bedroom.

I recently discarded an entire library. While there are still books in every other room in my house, those in the basement had been there since the early 2000s when I started a collection of non-fiction for my kids after my local library did a massive shelf cleaning. Maternal instinct found dangerous companionship with my inability to walk away from a free book and the basement shelves were soon filled with a treasury of vintage books about animals, historical figures, science projects, art history, and jokes.

They were never read. My kids have never been fans of non-fiction which I’ve always found puzzling. Although I grew up on the Oz series, Dr. Seuss, Babar, Laura Ingalls Wilder, and Aslan & the Pevensies, I was also a voracious consumer of non-fiction. I believe my lasting interest in the genre was born on a long Sunday afternoon during an encounter with a biographical series I discovered in the room of my older brother. The Clara Barton story in the collection might have been fictionalized, now that I think about it, but reading a book about an actual person was, for me, a revelation.

My thirst for knowledge of the real never altered so I suppose it makes perfect sense that when time came for me to write my own book, it was non-fiction, the first in the Chicago Review Press’s women’s history series, “Women of Action.” I’ve written five books for the series and was recently down in the basement, cleaning, because I’d just turned in my final contribution; I always crave physical, organization work after meeting a book deadline and, ironically, I turned from one non-fiction project to another.

As I sorted through the basement library, I found it a little sad to think that these books, while read by some children at some point in time, were never read by my own. But as they are all avid bibliophiles (and some aspiring writers), I have no cause for complaint. I’ve thrown away the moldier-smelling titles, donated others to my local little libraries (someone will surely value them!), and will use the rest in book-related crafts—I still have a long way to go before my brain feels balanced and I stop craving physical work.

I’m not sure what my next contract will look like but surely there are other books about the real world to be written, histories and biographies that will inspire younger readers. Perhaps these books will one day find themselves in a neglected basement library, but I hope not before being responsible for causing a few readers, at least, to understand that non-fiction can sometimes be stranger—or at least just as fascinating—as fiction.

2

2

More advance praise for my latest book

"The Vietnam War was hardly an all-male event. There were women participating on all sides of this war. Kathryn Atwood has collected the personal stories of a good sample of the women involved and her book is well worth reading for a look at the untold stories of the war."

--Joseph L. Galloway, co-author:

We Were Soldiers Once...And Young

We Are Soldiers Still

Triumph Without Victory: A History of the Persian Gulf War

"It is with a heart full of gratitude that I offer my thanks to Kathryn Atwood for bringing to light these women’s stories from the Vietnam War in her book Courageous Women of the Vietnam War: Medics, Journalists, Survivors, and More (Women of Action). Remembering their courage and resilience in the face of war remains of utmost importance."

--Kim Phuc Phan Thi, author of Fire Road: The Napalm Girl's Journey Through the Horrors of War to Faith, Forgiveness, and Peace

Advance praise for my latest book, Courageous Women of the Vietnam War:

"A moving tribute to the brave and often unacknowledged contribution of women during the Vietnam War, from nurses to surgeons, guerilla fighters to peace activists, journalists to survivors. Atwood honors heroines from all sides of the conflict, highlighting the common courage and humanity of the the women who struggled for survival and compassion in the midst of war. Courageous Women of the Vietnam War is an inspiration!"

--Kate Quinn, award-winning author of The Alice Network

“Kathryn J. Atwood's study of women in the Vietnam War is a welcome addition to the oral history of that fascinating and often tragic era. Atwood provides ample contextualization for younger and general readers while offering new, multiple perspectives on the complicated role of women in war for historians to ponder.”

-Frank Kusch, author of All American Boys: Draft Dodgers in Canada from the Vietnam War and Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention

The Beautiful Heart of Wonder Woman and Two Real Women Who Tried to Help the Belgians

Wonder Woman is a stunning film. And apart from the first Captain America, its plot was one of the few in the super hero genre that I could actually follow, perhaps because the story line wasn’t convoluted and perhaps because I was already familiar with many aspects of the film’s setting. I was enormously impressed by how many things the film got right about that setting including one element of World War I of which we Americans seem to know little: the German occupation of Belgium.

The film might have been just as successful had it focused solely on military elements, had Diana, Princess of Themyscira, charged through no-man’s-land merely to defeat the enemy at hand. But she deflected German bullets during that spectacular scene for a very specific reason: she was determined to rescue oppressed Belgian civilians. For despite her stunning good looks, what made Diana truly beautiful was her empathy: her heart for the downtrodden, the wounded, the helpless. While her strength and indestructible weapons gave her super-human abilities, her heart put me in mind of two real women who also took it upon themselves to help Belgian civilians during World War I.

When the war was just months old, famed American mystery author Mary Roberts Rinehart sailed to England before visiting the tiny sliver of unoccupied Belgium. Although her initial motive had been to seek out adventure, what Mary witnessed during her hospital tours immediately transformed her into an empathetic chronicler of the war’s devastating effects on the Belgians:

Never in all that time did I overcome the sense of unreality, and always I was obsessed with the injustice, the wanton waste and injustice of it all. The baby at La Panne—why should it go through life on stumps instead of legs? The boyish officer—why should he have died? The little 16 year-old soldier…why should he never see again? Why? Why? (1)

Mary also visited the Belgian army’s front-line trenches where at one point she was close enough to the German line to distinguish individual sand bags. But what she considered the tour-de-force of her trip was an hour-long interview of King Albert who Mary described as “a very big…blond young man, very patient, very worn.” (2) She initiated the visit because she wanted to confirm the rumored reports of German atrocities against Belgian civilians during the invasion and occupation.

"It would be unfair," he said, "to condemn the whole Germany army. Some regiments have been most humane, but others have behaved very badly…" Then the king confirmed a story that Mary had heard regarding the Germans using Belgian civilians as human shields as they advanced. “It is quite true,” said the king, when Mary asked him about it. “When the Belgian soldiers fired on the enemy they killed their own people. Again and again innocent civilians of both sexes were sacrificed to protect the invading army during attacks.” (3)

Mary turned the interview into a report and her notes into a book called Kings, Queens and Pawns: An American Woman at the Front, hoping that her pen and fame might save the Belgian people by way of budging American neutrality. It did nothing of the sort; the United States wouldn’t enter the war until 1917 and for very different reasons.

But Mary, like Diana, was an empathetic outsider. Gabriel Petit, on the other hand, was a Belgian. Born into a broken, blighted home, Gabriel was on her own at the age of 15 and at 20 survived a suicide attempt. However, just before the German invasion in August, 1914, her life was starting an upward turn; she was taken under the kind wings of an elderly couple in Brussels and became engaged to a Belgian soldier.

When the war began, Gabriel’s surrogate father died and her fiancé was wounded. All her hard-won happiness threatened, Gabriel took action: she immediately joined the Red Cross and collected funds for the Belgian Army, both door to door and in public places, writing to her fiancé: “Considering I have a lot of nerve, I do a very good business.” (4)

But when Brussels was overcome and occupied, Gabriel left Belgium to find her fiancé who had escaped to France with his regiment. During this trip, Gabrielle discovered a vocation far more powerful than fundraising: she was recruited by a British Intelligence officer. After two weeks training in London, she returned to Belgium as a spy.

It was while working for the British--taking note of German troop movements and bridge widths, distributing underground newspapers to boost morale, and helping her fellow Belgians escape--that the passionate young woman discovered her true love:

My country! I did not think enough of it, I almost ignored it. I did not see that I loved her. But since they torment her, the monsters, I see her everywhere. I breathe her in the streets of the city, in the shadow of our palace…she lives in me, I live in her. I will die for her singing. (5)

Although Gabriel didn’t die singing, legend does have her shouting: after six months of successful espionage work against the Germans, she was caught, tried, and executed by German firing squad. Her defiant behavior during the final weeks of her life became a unifying national symbol for a devastated and divided post-war Belgium (and a symbol of resistance for that nation when it was once again occupied by the Germans during the Second World War.)

Unlike Wonder Woman, Mary Roberts Rinehart and Gabriel Petit did not possess indestructible weapons and super-human strength. But like the inspiring heroine of the recent film, they both had great hearts and courageous compassion which propelled them to do everything in their power to make a difference in the lives of the oppressed Belgian civilians of World War I.

Notes:

1. Kings, Queens and Pawns: An American Woman at the Front, 49.

2. Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies, and Medics, 193.

3. Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies, and Medics, 193.

4. Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies, and Medics, 55.

5. Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies, and Medics, 58.

1

1

The Pacific Theater and the Cost of Heroism

“Heroism is endurance for one moment more.”--George F. Kennan

Back in 2010, I told an acquaintance that I had just finished a WWII collective biography, due out the following year. She immediately began enthusing about a WWII book she’d been reading and asked if I'd also read it. I hadn’t and the way she described it—a WWII flyboy who becomes lost at sea before being nearly tortured to death in a Japanese POW camp—didn’t particularly pique my interest.

My personal images and interest in WWII—as well as the book I was working on--all focused on the European conflict. My Army Air Corps dad and his three brothers had all flown in the European Theater and while I was in high school The Hiding Place: The Triumphant True Story of Corrie Ten Boom had come to theaters. So the two basic images implanted in my mind regarding WWII—tall, dashing, Dutch-American flyboys and a middle-aged Dutch woman who defied the Nazis by hiding Jews—had, apart from Pearl Harbor, made me consider WWII as a primarily European conflict and had compartmentalized the war in my brain under the category of courage, not necessarily endurance.

Louie Zamperini, on the other hand, the subject of my friend’s favorite read, had gained hero status in the Pacific Theater by what he’d endured: a sadistic Japanese officer named named Mutsuhiro Wantabe became determined to break him. Zamperini shouldn’t have survived. He did.

When I decided to write a book focusing on the Pacific War, reading Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption became one way in which I immersed myself in the general topic. Like so many others before me, I was mesmerized by the tale and Laura Hillenbrand’s masterful storytelling. And in the process of reading the book, along with the memoirs and biographies of the women featured in what would become Women Heroes of World War II—the Pacific Theater: 15 Stories of Resistance, Rescue, Sabotage, and Survival, I came to understand that endurance was precisely what the Pacific War had been for millions of people; not only for American troops fighting an enemy who refused to surrender, but for the civilians unfortunate enough to find themselves in Japanese-controlled territory.

Trying to implement their “Asia for Asians” mantra, the Japanese invaders/occupiers rounded up all Allied civilians into camps. While a far cry from the Nazi-run concentration camps, these Japanese internment camps were full of disease, starvation, and yes, endurance.

One fascinating way in which a group of imprisoned British and European civilians and Australian army nurses sought to maintain the health of their spirits was by something called the vocal orchestra. A choir-without-words initiated by two brilliant musically-inclined inmates who created a repertoire of orchestral pieces such as the Largo from Dvorak’s New World Symphony, the vocal orchestra was a brilliant antidote to the despair pervading the diseased camp.

Humans needs food and medicine as well as encouragement, especially when living in a tropical environment, and because the prisoners had little of either, the vocal orchestra literally died out long before the war’s end. But its impact was beautifully captured in the memoir of Helen Colijn, a Dutch teen featured in Women Heroes of World War II—the Pacific Theater: 15 Stories of Resistance, Rescue, Sabotage, and Survival.

Three women featured in my book perhaps fit more precisely into the Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption category because they, like Zamperini, endured intentional physical torture. Elizabeth Choy, Sybil Kathigasu, and Claire Phillips all suffered at the hands of the Kempetai, the Japanese military police, who, like the German Gestapo, were tasked with weeding out resistance activities.

Elizabeth Choy found herself in their hands inadvertently after she had unknowingly passed radio parts to Allied prisoners in Singapore. The Japanese were convinced she was part of a larger plot so to obtain the desired confession, they tortured her nearly to death. Deeply religious, she refused to lie, even to save her life.

Sybil Kathigasu, on the other hand, was an active member of the Malayan resistance: she provided medical care to local guerilla fighters. She was caught and taken into Kempeitai custody where one officer named Eko Yoshimura took a special interest in breaking her. He nearly destroyed Kathigasu's body but her will remained intact and she never divulged the information Yoshimura sought.

Claire Phillips, an American member of the Manila resistance, charmed and chatted up Japanese officers in her nightclub, gleaning precious tidbits of intel, then used her earnings to sneak food to starving American POWs. She was caught, interrogated, tortured, and starved by the Kempeitai for nearly nine months without betraying anyone.

There was often a long-term cost for defying Imperial Japan. When I finished Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption, I realized that the book’s title was a bit of a misnomer. Yes, Zamperini survived Wantabe’s beatings. But years after the war, the brutal Japanese officer was still in his head, tormenting his dreams so much that the American hero, now a full-fledged alcoholic, was convinced that the only way to peace was an airplane ticket to Japan so he could kill Wantabe.

Conversion to Christianity saved Zamperini from his dark spiral but not all American Pacific War POWs fared as well: they suffered far more PTS, alcoholism, premature death, suicide, and divorce in comparison with their counterparts released from German camps.

I found a similar trend among the women whose stories I encountered while writing my book. Sybil Kathigasu died three years after the war from complications arising from her beatings and Claire Phillips died in 1960 from alcoholism-related meningitis. Even women who hadn't been imprisoned during the war were powerfully and negatively impacted by it. Yay Panlilio, part of an anti-Japanese Filipino guerilla force, claimed post-war that the conflict had completely worn down her body, mind, and emotions. Gladys Aylward's health remained precarious for years after she'd personally escorted Chinese war orphans to safety during a long, dangerous trek. Minnie Vautrin, an American who exhausted herself trying to protect women during the horrific Nanking Massacre, eventually committed suicide.

All war creates suffering in the moment and in the aftermath. This was especially true for the Pacific Theater, which is why America's general lack of familiarity with the conflict's details is so tragic. After all, the victims of Japanese fascism--or those who became heroes defying it--deserve respect and remembrance just as much as their counterparts in the European Theater.

Louie Zamperini once dismissed his war hero status, claiming that mere survival does not make one a hero. Millions of his fans--myself included--profoundly disagree. Surviving the Pacific War was more than enough to earn the designation.

2

2

American Teens Encounter the Women of World War I

I had the opportunity this week to come face-to-face with a slice of my target audience: teenagers. They heard the heroic story of French teen Emilienne Moreau before viewing a sizeable number of archival photos depicting German, French, British, Italian, and American women at work on the home front, in munitions factories, in the medical services, and in auxiliary military roles.

They also learned the surprising connection between the Russian Women's Battalion of Death and American suffragists: how the existence of the world-famous Russian battalion refuted the American "Bullets for Ballots" anti-suffragist slogan.

Their teacher asked them what they found the most interesting and here's what some of them had to say:

- "I found it very interesting that women inspired each other from World War I to World War II. It was also very interesting learning about the women because I never hear about women heroes" - Emma

- "I found the story of Emilienne Moreau and how France and Britain use her story for their own benefit most interesting. I think it should be a requirement to include important female heroes in textbooks." -Leah

- "I thought it was interesting that a teenage girl in France was a school teacher that was able to also be a hero. I am only three years younger than she was at the time!" - Sophie

- "Emilienne Moreau's story was really interesting because it showed how governments twisted stories of heroes in their favor." -Lilly

and on the same topic -- "...it was amazing how brave and selfless she was."

-Emma

- "The Russian women's battalion of Death because of the huge impact they made (This was a response shared by many students)

- "I found the books interesting and would like to read one one day." - Maggie

- "What I found interesting is how much World War I helped women get more jobs." - Derrick

- "I liked hearing all the courageous stories about women fighting in the war." - Lincoln

- "So many woman were helpful to the war effort and broke so many barriers that were thought to be indestructible." - Eva

- "What I found most interesting was how so many women helped out in the war, whether it was being a nurse or a factory worker or a number of other things."

- "I liked when she listed all the things women did when the men were at war because I found it interesting to learn about what they did back then."

- "Emilienne Moreau and her story was inspiring and very interesting and courageous."

- "How all of the women were somehow connected. Some women joined [WWII] because they were inspired by [WWI] women, or they read memoirs, and were motivated."

- "Feminine power even though they couldn't vote yet."

- "The amount of jobs that opened up - especially that women participated in the Army and Navy, and some [in the US Navy] got paid as much as men. This is very surprising because women didn't work as much, it was less common, so the fact that they got equal pay is surprising. Even today we have issues with gender equality and pay."

- "I found all of the stories in the war effort very interesting because that is something we don't see in our textbooks. We only read about male heroes in World War I, but women played a big role."

2

2